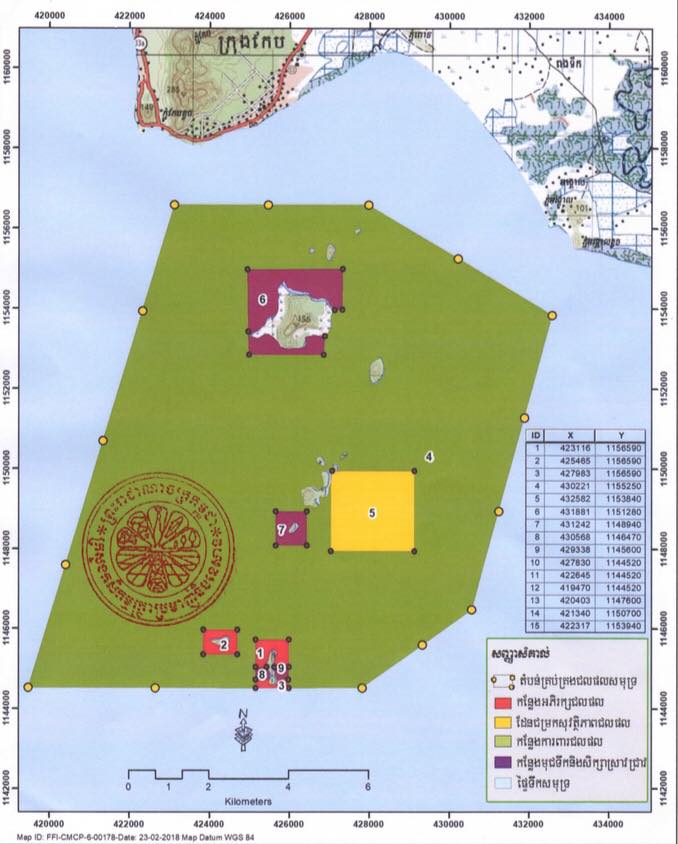

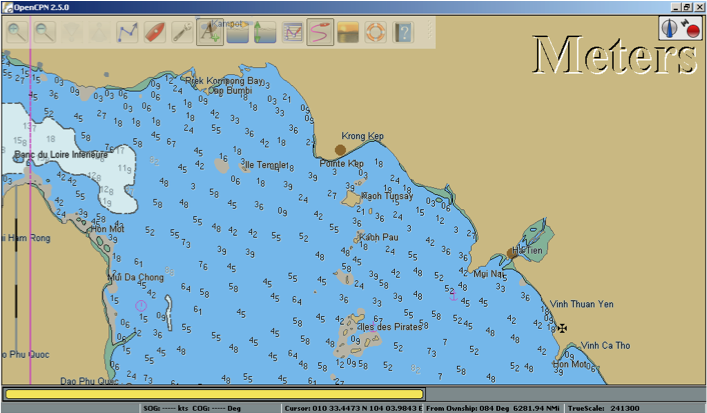

After 4 years of hard work, frustration, struggle, passion and dedication, the 11 354ha Kep MFMA was nationally proclaimed in April 2018. This was a huge step forward for the protection of the Kep Archipelago, and for Cambodia.

After 4 years of hard work, frustration, struggle, passion and dedication, the 11 354ha Kep MFMA was nationally proclaimed in April 2018. This was a huge step forward for the protection of the Kep Archipelago, and for Cambodia.

What is Plastic Pollution?

Plastic Pollution is the contamination of the environment by plastics. Plastics are synthetic organic materials produced by polymerisation. Worldwide plastic production has increased from 1.5 million tonnes a year in 1950 to 322 million tonnes a year in 2015. Due to rapid urbanisation and economic development in a market driven by consumerism and convenience, along with the relatively low price of plastic materials, there has been a rapid increase in the generation of waste plastics all over the world. This is a major environmental concern for three main reasons: dependence on fossil fuels, solid waste clogging up ecosystems and microplastics.

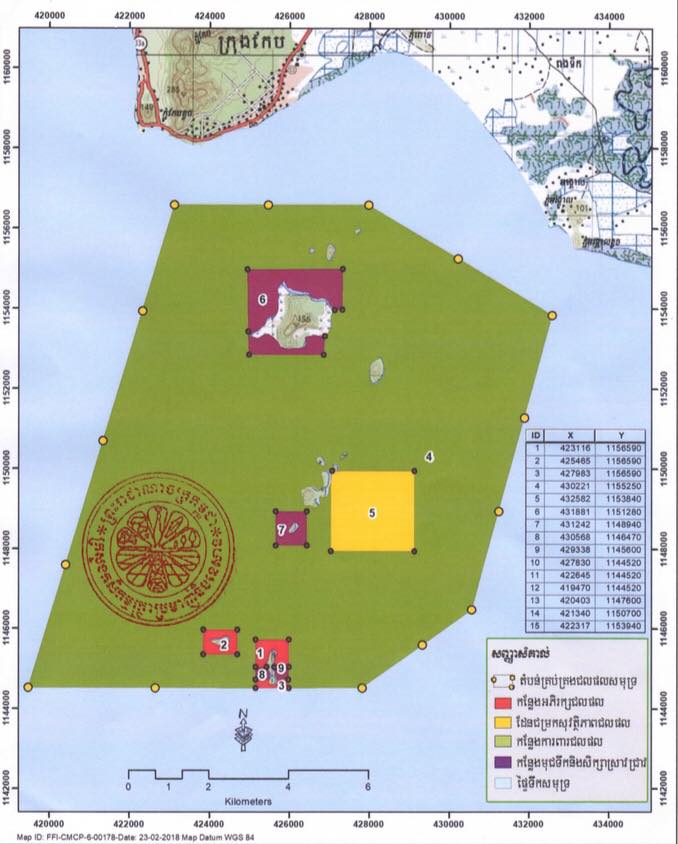

What are plastics?

One of the main characteristics of plastics is the fact that they come in many different shapes, colours, sizes and, most importantly, chemical compositions. This is a major problem when it comes to recycling, as the wrong type of plastic can contaminate recycling streams and not all types are recyclable.

Thanks to legislation, most plastics products are now labelled with symbols representing their chemical composition. This can help sort them in to different categories, applications and properties.

Why Plastics are a problem ?

At the moment, over 95% of plastics are produced from fossil fuels. Around 4 percent of oil consumed worldwide is used to make plastic, with another 4 percent being used in the manufacturing process. One of the leading contributors to climate change and habitat destruction around the world is the dependence on fossil fuels.

Plastics do not biodegrade: they do not decompose naturally in the environment. Plastic waste is either put in landfill where it can contaminate groundwater by leaching harmful chemicals, incinerated which releases toxic chemicals into the atmosphere (Dioxins, Furans, Mercury and Polychlorinated Biphenyls), or littered. Because of plastic’s lightweight and durable nature, it is very likely to be swept into waterways, making its way from cities to the sea. Plastics reduce the productivity of natural systems such as the ocean.

Some scary stats:

• The equivalent of one garbage truck of plastic waste is dumped into the ocean every minute

• If no action is taken, this is expected to increase to two per minute by 2030 and four per minute by 2050

• In a business-as-usual scenario, the ocean is expected to contain 1 tonne of plastic for every 3 tonnes of fish by 2025, and by 2050, more plastics than fish (by weight)

• 100,000 marine mammals die each year from plastic pollution

Microplastics

In marine environments, the combined effects of UV radiation, chemical degradation, wave mechanics and grazing by marine life weakens plastics, causing them to fragment into increasingly smaller pieces known as microplastics. Microplastics can be found everywhere: from sea surface to the sea-floor, in deep-sea sediments and even in Arctic sea ice. They create a smog of debris in seawater and are mistaken for food by plankton, birds, fish and other marine animals. They have even been found in table salt, and the average shellfish consumer ingests 11,0000 microplastic particles a year. Microplastics soak up chemical additives and endocrine disruptors, and act as vectors for pathogenic bacteria. The complexity of estimating toxicity means potential risks to human health not yet known. Given the presence of heavy metals and other concerning chemicals, it is however wise to limit the entry of plastic into the food chain.

The fact that microplastics absorb endorcine disruptors means that when ingested, they can affect correct hormone function. Hormones in the human body regulate digestion, metabolism, respiration, tissue function, sensory perception, sleep, excretion, lactation, stress, growth and development, movement, reproduction, and mood.

Microfibres

Microfibre pollution is an example of how little we know about the extent of the plastic problem. Microfibres are microscopic fibres released into waste water systems by washing machines when we wash our clothes. They originate from a wide variety of synthetic textiles (such as nylon, polyester, rayon, acrylic or spandex)—everything from running shorts to yoga pants to fleece jackets and more—which shows the need for engagement on this issue by the entire apparel industry and through all steps in the product life cycle.

Garments of a higher quality shed less in the wash than low-quality synthetic products, illustrating the importance for manufacturers and consumers alike to invest in gear built to last.

Where do plastics come from?

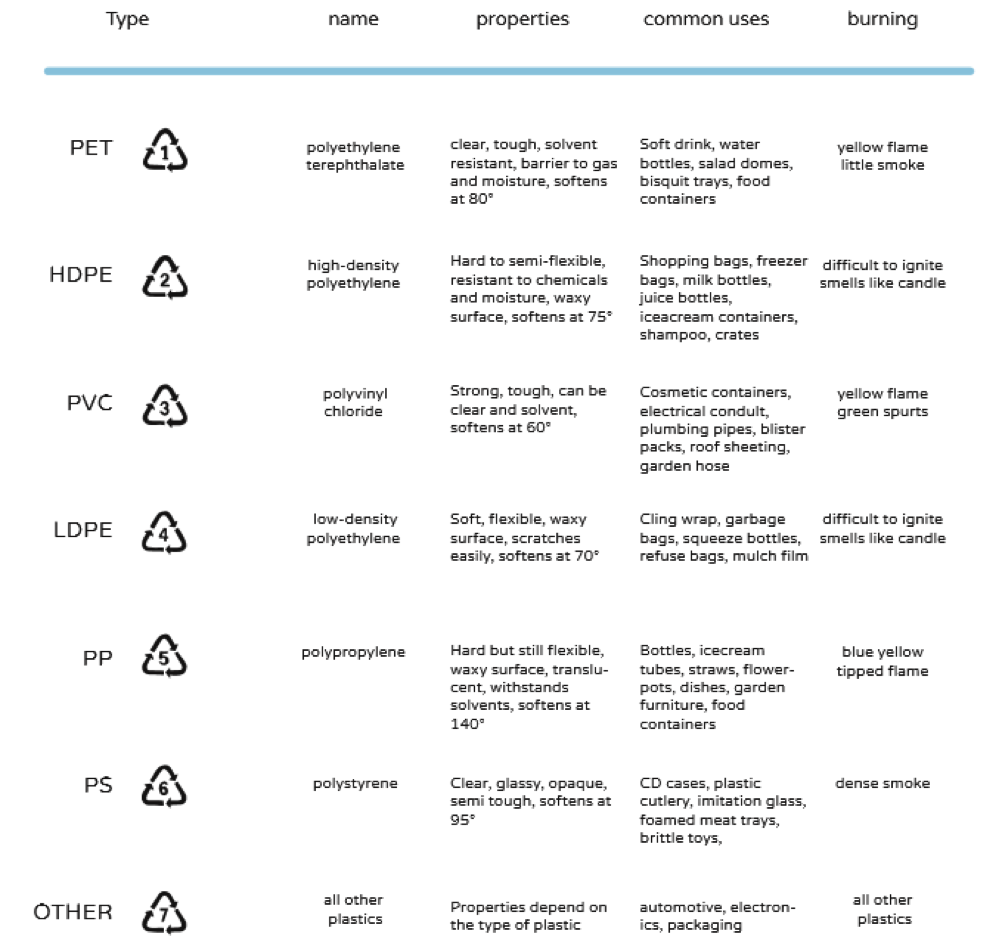

Plastics have many necessary and positive applications, such as food preservation, medical uses, and infrastructure. Most plastic waste does however not fall into this category. Almost 50% of all plastic waste is made up of ‘disposable’ single use-packaging. This is completely unnecessary: how can you call it disposable if it never goes away?

Some of the usual suspects include: cosmetics bottles and microbeads in exfoliant soap, bags, straws, bottles, cutlery, cups, wrappers, and take-away containers.

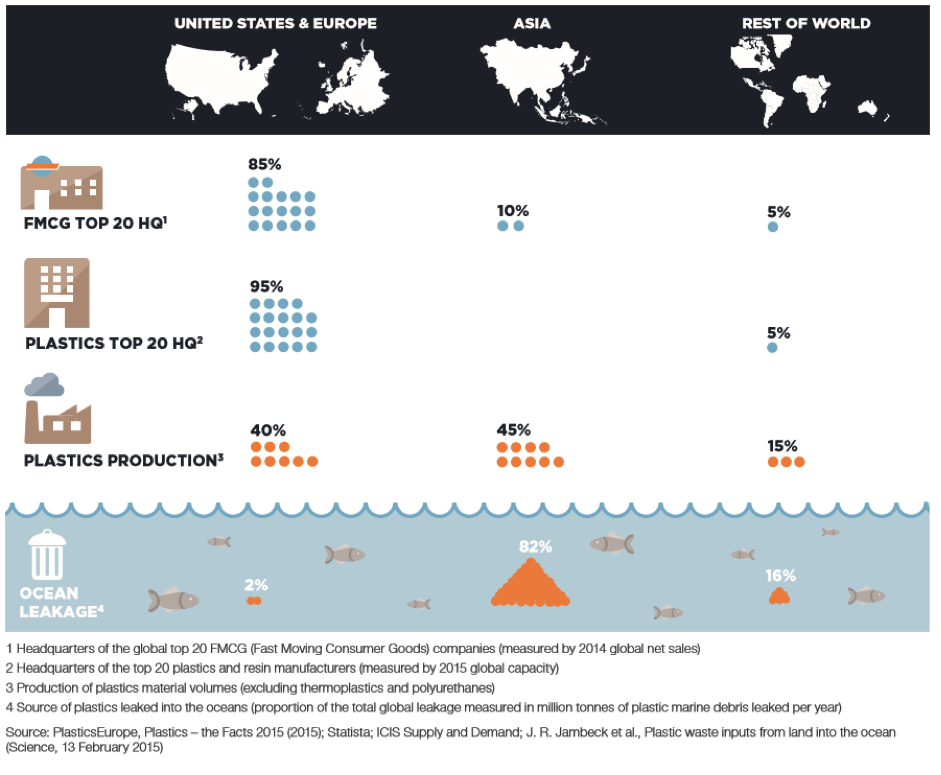

Although all this plastic is not designed or produced in Asia, 82% of leakage into the ocean occurs in Asia. This could be because of lack of infrastructure, waste management and recycling plants. Another reason for this is the extensive coastlines in this part of the world. Let’s not forget either that 87% of Europe’s ‘recycling’ gets sent to China. This increases the risk of spillage during transportation, and there is insufficient understanding of what happens to the waste plastics once they arrive in China, which raises concerns about the implications on local and global health and environment.

The Mekong river has been identified as one of the main rivers worldwide contributing to ocean plastics. This highlights the importance of implementing change in this part of the world. Changing behaviours through education, improving waste collection infrasctructures and introducing new legislation in Asia will prevent vast amounts of plastic waste from reaching the ocean.

What can we do?

• Demand stricter regulations

If enough of us make our governmental representatives realise how much we care about this issue, policy makers can influence producers and instigate widespread, far-reaching positive change. Signing petitions and staying informed is important.

• Spread awareness

Talking about the issue to friends and family, at work or at school, can help spread awareness.

• Change behaviours

It is important for every individual to adopt new habits such as always carrying a reusable bottle, bag, and straw.

• Avoid single-use plastics

We can all help by avoiding single-use plastic in our day to day life. At the supermarket, choose products not wrapped in plastic.

• Organise clean-ups

Leading by example and cleaning up your own local neighbourhood, beach or riverside can have a ripple effect on the community. By normalising the beahaviour of caring for the place we live in, others will start to do the same.

What’s stopping personal change?

Psychological barriers to sustainable consumption

• ‘Choices’ in consumption are in fact habitual behaviours

• Consequences of consumption choices hard to see

• Sustainable consumption may not seem personally relevant

• Behaviour strongly influenced by social groups

• Hard to follow through on sustainable choices

What is MCC doing?

MCC

Non-profit organisations and grassroots campaigns can engage communities and influence policy makers.

Mass communication should not be limited to major high technology and professionalism. An example of alternative mass communication is street art. Street art here incorporates murals, posters, graffiti, placards, banners and stickers employed by collectives as a communication device for persuading and informing. Human emotions and political views can be shaped and moved by street art, which has a long political social history.

Therefore, MCC is working on a mural project in Kep, which will be accompanied by the dissemination of informative posters and at events relevant to the sea.

On the island of Koh Seh, arts and crafts with plastic from beach cleans are a creative and functional alternative to the incineration of them. we run daily clean ups around our island and organise large joint clean ups on Kep Mainland beaches.

Volunteers with Experience or Interest in MPA or fisheries resource management.

We are just beginning a whole new stage in the development of our conservation efforts in Kep province. Our MFMA (Marine Fisheries Management Area) zoning proposal has been accepted and over the next few months we will be adapting finalizing our current management plan, this includes registration of fishers, catch monitoring, demarcation, quotas on size and sexual maturity, and a full MCS program to deter and stop any IUU activities with in the proposed zones.

You will be contributing to the second MFMA in Cambodia (Our work in Koh Rong Samloem was integral to the creation of Cambodia’s First MFMA). The management of this smaller area will be faster and easier to implement and also allows us more freedom to think outside the basic management structures and trial a series of restoration projects.

Volunteers with Experience or Interest in IUU (Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported) fishing and MCS (Monitoring Control and Surveillance).

We are currently working on many reports directly relating to these current issues.

This is a great opportunity to be directly involved in on the ground activities, our work makes a direct impact. And the work you would be contributing to is history in the making.

We have received some much needed initial funding from the International conservation fund of Canada (ICFC) which covers our work combatting IUU, but also includes our first initial budget for creating these structures. We would like to thank ICFC for being there in our time of need and continuing to make this work possible. We are still however looking for more funding to grow and maintain this project. Here is a small rundown on what we have begun and hope to achieve in the future.

INTRODUCTION

The consequences of the global decline in shellfish reefs has largely remained under the radar of the scientific and conservation community. Shellfish reefs provide a large range of ecosystem services, including habitat and food provision, coastal defence, nutrient cycling and water filtration. Restoration of shellfish reefs in Kep Province, Cambodia, would catalyse the enhancement of its vulnerable marine environment. Importantly, aside from enlarging commercial marine species populations, this would create opportunities for aquaculture that would greatly benefit small-scale fishing communities. These opportunities would additionally extent to current illegal fishers, thereby addressing this pervasive issue in Kep Province.

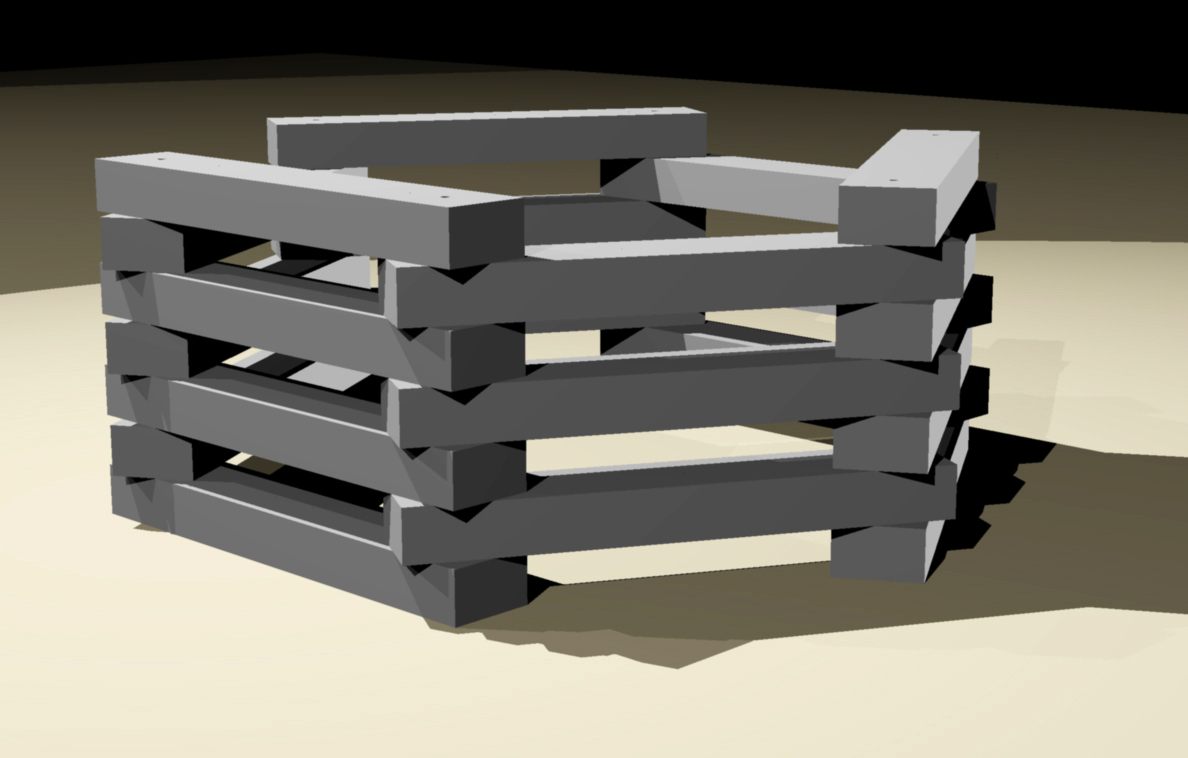

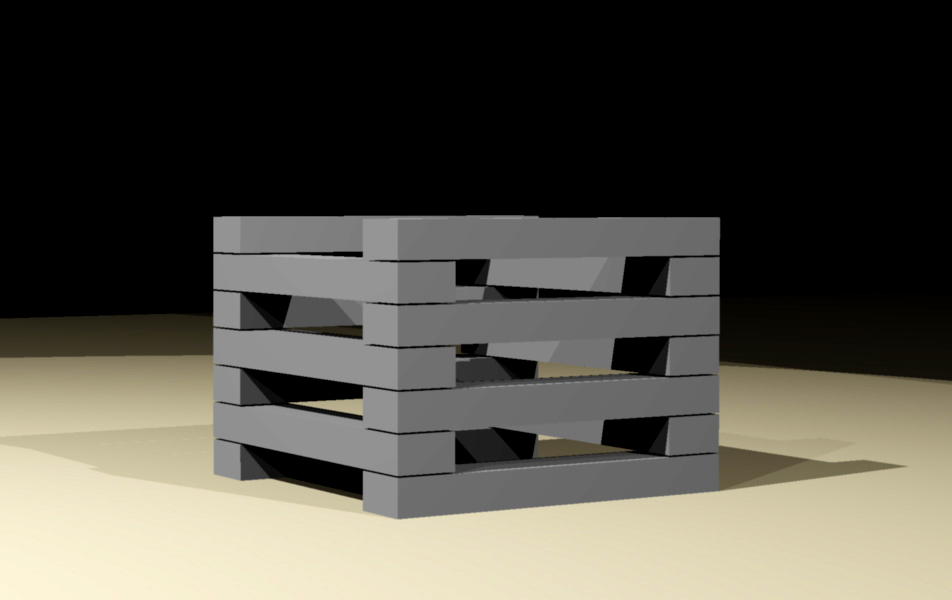

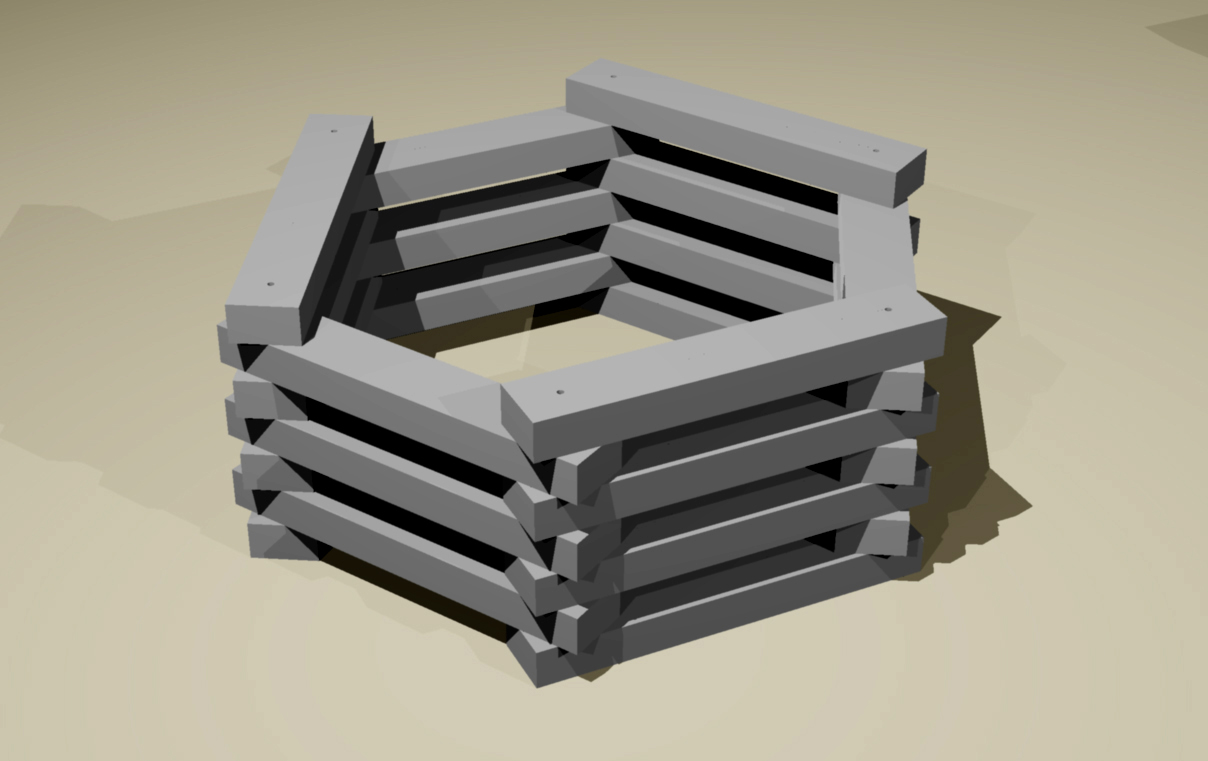

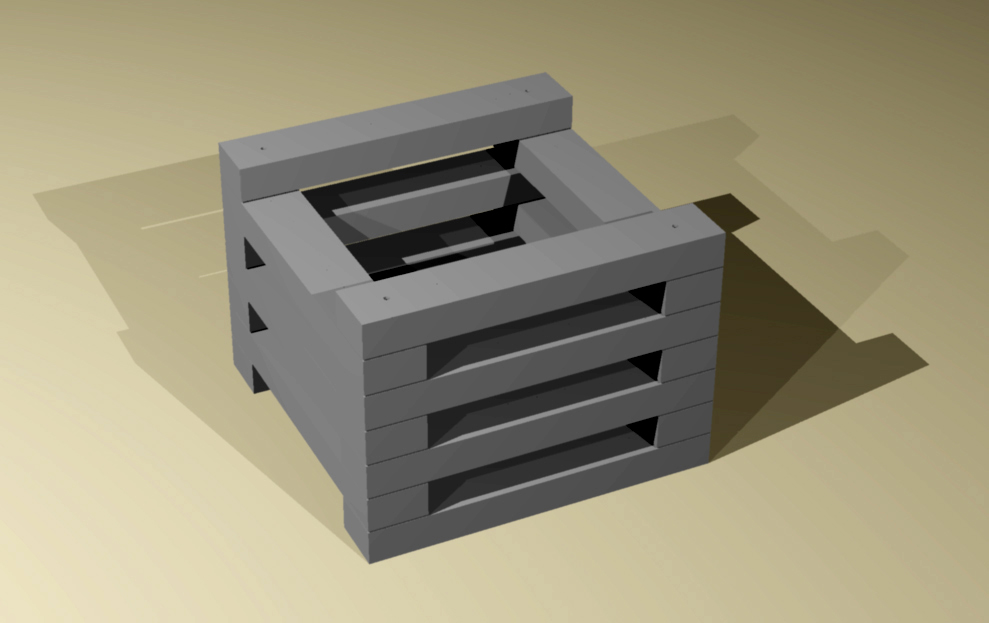

We are currently undertaking a pilot project on Koh Seh, Kep Province, in which artificial reef structures will be created and deployed within MCC’s legislated conservation area. The main purpose of these structures is to provide substrate for oyster and mussel growth. This project will provide invaluable experience in setting up and maintaining shellfish reefs, and if successful, could be expanded long-term throughout Kep Province.

Bivalve shellfish reefs and beds (hereafter called reefs) were once abundant throughout many parts of the world, including North and South America, Australia, New Zealand, China, Korea and Japan. These reefs suffered dramatic decline (85% of oyster reefs lost globally), which is thought to be primarily a result of overharvesting, coastal development and the introduction/trans-location of non-native shellfish species. Conservationists and the scientific community are only recently beginning to study and realise the variety of important economic and ecological advantages that these reefs can provide. Oysters are considered ecosystem engineers, and perform numerous invaluable ecosystem services. Examples include stabilization and protection of shorelines, food and habitat for fish species, improving water clarity and quality, removing excess nutrients and sediment on top of the variety of short and long-term employment opportunities available for coastal communities and tourism industries. This realization, in conjunction with the alarmingly low level of functional shellfish reefs remaining today, has spurred a series of projects attempting to restore and protect these reefs in the Gulf of Mexico, Australia, the United States and China.

Shellfish reefs are still present in Cambodia, and despite a lack of documentation detailing historic shellfish distribution, they have very likely faced heavy decline. This most likely occurred predominately through overharvesting and intensive bottom trawling of shallow waters. Most declines start with destruction of the primary structural complexity, often through dredging/trawling, which increases likelihood of stresses from anoxia, sedimentation, disease, and non-native species1. Trawling results in extensive habitat damage and poor environmental conditions in Kep Province, and Marine Conservation Cambodia (MCC) has witnessed a numerous trawling nets with high by-catch of oyster and mussel species (see picture…). It is very plausible that this destructive fishing technique caused widespread elimination of natural shellfish habitats in Kep Province. Despite this, MCC believes that trawling vessels will not have a noteworthy effect on the artificial reef structures for a number of reasons. Vessels will be hampered from trawling through the artificial reef structures proposed in this document, due to the sheer weight and size of the structures, as well as the close proximity regarding placement. In addition to this, demarcation through buoys will aid fishing vessels in general to avoid the water nearby these structures.

The restoration of these reefs will form a significant step in revitalizing Kep’s marine environment and ensuing economic benefits. Shellfish reefs are associated with high levels of species diversity and unique assemblages, and improved water quality, thereby enhancing Kep’s marine environment. In light of Kep’s extensive seagrass decline and recent algae bloom, the ability to shellfish reefs to facilitate seagrass growth and hinder the probability of harmful algae blooms is especially relevant. By acting as natural coastal defence mechanisms, shellfish reefs will assist in mitigating the consequences predicted to result from sea level rise via climate change. This is especially important in ensuring security for Kep’s and Cambodia’s coastal communities in the near future. Shellfish reefs will provide opportunities for private sector input, which leads to further development of and improvements to the creation, management and monitoring of these reef structures. In turn, this may increase the productivity and commercial species biomass of these reefs, which ties back into further private sector involvement, as well as more widespread benefits to other stakeholders.

Small-scale fishers and their families, who rely on marine resources for their livelihood, will be the primary beneficiaries of these shellfish reefs. Cambodia’s marine fisheries are in a declining state, yet reliance upon them is only increasing. Sustainable aquaculture is a necessity to mitigate the looming detrimental impacts that are likely to ensue upon fishing communities and coastal provinces if action is not taken.

Evidently, the formation of shellfish reefs in Kep Province will benefit several parties, including fishing communities, aquaculture and tourism industries, and government bodies. Alternative employment for illegal fishers or those experiencing economic hardship will also be readily accessible, helping to address this ongoing issue.

MAIN TARGET SPECIES

MCC has identified two local shellfish species for restoration and potential future commercial harvest; the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and green lipped mussel (Perna canaliculus). The Pacific oyster is native to Japan and South East Asia, and occurs primarily in marine and estuarine habitats. This oyster is globally a popular choice for bivalve aquaculture, given its characteristic rapid growth (market size in 18 to 30 months), wide range of tolerances to environmental parameters, and lack of major issues with disease. The water conditions at Koh Seh are suitable for Pacific oyster growth, with the temperature (27 – 33ºC) and salinity range (2.9 – 4.1%) falling within the Pacific oyster’s spectrum of physiological tolerances. The green lipped mussel is widely distributed in the Indo-Pacific region throughout estuarine and marine habitats. However the installation of these devices will go far beyond just our main target species.

CREATION and DEPLOYMENT

Creation and deployment of artificial reef structures is taking place on MCC’s current base island on Koh Seh, Kep Province, Cambodia. Specifically, these structures will be placed within MCC’s 300m by 150m conservation and research area on the eastern side of Koh Seh. The marine habitats within this side of the island sequentially consist of shallow fringing reefs, seagrass, sand and shell, and mud. The depth ranges from 0.5m to 4m, with the maximum occurring in the mud habitat. Artificial reef structures will be placed in a specified range ending at the eastern extent of MCC’s conservation zone (approximately 300m from shore), where the habitat is predominately mud resultant from trawling. MCC has held legal jurisdiction over its conservation area for the past 3 years Before MCC’s placement on Koh Seh, unsustainable fishers using methods such as trawling, shell collecting, long-lines, rat-tail traps, and in the past cyanide and dynamite fishing, frequently damaged the reef structure and ecosystem of this island. Since MCC’s restoration efforts on the island began (December 2013), the intensity of illegal and destructive fishing techniques has lowered significantly. In saying this, illegal fishing boats are still active within Koh Seh’s eastern marine environment, consisting predominately of shell collectors and less often, trawlers. MCC’s efforts, in conjunction with improvements in marine law enforcement by local fisheries departments, have resulted in noteworthy enlargements in fish biodiversity and abundance, as well as ecosystem health in general. This improvement has been noticed by local small-scale fishers, who are often present within this area and typically use sustainable gear. MCC strongly believes that the marine environment on the eastern side of Koh Seh is suitable for sustained shellfish growth on the artificial reef structures. Nutrient levels are relatively high… Reinforcing this is research evidence from MCC’s coral reef surveys and personal observations that the ecosystem is in a state of increasing recovery. In addition to this, oysters and mussels already grow within this vicinity. Despite illegal fishing methods still utilized within MCC’s conservation area, MCC believes that the level of these activities is sufficiently low, so as not to greatly impair the effectiveness of the artificial reef structures.

Creation of the blocks picture gallery.

Our Full Project Concept and Proposals are available on request for potential funders. Contact Us

This project also opens up many new opportunities for potential interns and volunteers, with regards to aquaculture and research on the impacts and scope of the restoration.

Illegal:

Illegal fishing refers to activities that are in violation of regional, state, national or international laws/obligations. This includes foreign or national vessels operating without permission in waters under the jurisdiction of a State, or against the relevant measures adopted by a RFMO. Illegal fishing in Cambodia has two sources; foreign and domestic. Both sources mainly occur in the form of destructive fishing techniques (e.g. pair trawling and electric trawling). Foreign vessels fishing without authority from their own flag State are also considered to be acting illegally. Domestic vessels which utilise mesh sizes below the minimum legal limit, banned fishing gear, or that lack registration or a license required to fish, are acting unlawfully. Furthermore, despite its alarming frequency, trawling in waters shallower than 20 metres is a criminal act.

Unreported:

Unreported fishing refers to those which have not been reported, or have been misreported, to the relevant national authority, in contravention of national laws and regulations. Additionally, it refers to the lack of reporting, or the misreporting, of fishing activities to the relevant RFMO, in contravention of the reporting procedures of that organization. Unreported fishing in Cambodia mainly refers to Thai and Vietnamese vessels that fish in Cambodian waters, as well as the lack of reporting of IUU fishing to the relevant authorities. Furthermore, the purposeful negligence of catch quotas and the misreporting of catch quantity/species is classed as unreported fishing.

Unregulated:

Unregulated fishing activities include those conducted in areas or targeting marine stocks where no relevant conservation and management measures are in place. Fishing activities that are carried out in a manner inconsistent with State responsibilities for the conservation and management of marine resources under international law, are also considered unregulated. Finally, vessels performing fishing activities within the domain of an RFMO without displaying nationality, or flying the flag of a State not party to the RFMO, are considered to be carrying out unregulated activities. Some examples of unregulated fishing in Cambodia include the large proportion of Cambodian boats without license or registration, open access fisheries and foreign vessels freely fishing in Cambodian waters with no impact assessment.

Other forms of IUU fishing activities include (Funge-Smith; SEAFDEC Secretariat 2016):

– Catching of prohibited or protected species.

– Fishing with a fake license, registration or vessel numbers.

– Registered boats that do not follow the relevant vessel specifications detailed in registration.

– Vessels carrying more than one flag, fishing in waters outside the permitted or designated fishing areas.

– Landing of fish in unauthorized ports or across borders.

– Transfer of catch at sea.

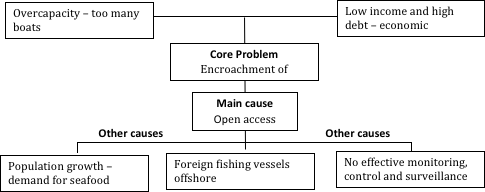

Clearly, IUU fishing can arise in an enormous variety of forms, whether through unlawful method, catch, documentation, vessel specifications etc. Numerous factors that catalyse the development of IUU fishing will be discussed, for instance overcapacity, low relative risk of punishment and open-access fisheries.

Factors leading to IUU fishing:

Overcapacity of fishing vessels is a major driver of IUU fishing in Cambodia (Funge-Smith). Marine resources are in decline and struggling to replenish due to frequent and intense fishing pressure. In this situation, fishers may be induced to utilise illegal and destructive fishing methods out of desperation for sparse marine resources. These methods are indiscriminate and frequently result in the capture of non-target species, which are composed mostly of prematurely caught juveniles (Ahmed & Chanthana 2015). For example, socio-demographic surveys conducted by MCC during August 2015 at Prek Tanean revealed that trawler by-catch can be higher than 80%, and also consists of habitat such as seagrass and coral. Catching low quantities of commercial species perpetuates overfishing, creating drastic declines in marine populations. Following this, illegal and destructive techniques may be used in an effort to capture scarce commercial species. Finally, this reduces population numbers further and destroys habitats, once again increasing the level of fishing intensity and fulfilling a perpetual cycle of ecosystem destruction. Furthermore, this cycle has been swiftly intensified by the rapid development of fishing technologies (Siriraksophon 2016).

Exacerbating the issues of overharvesting is the relatively low risk of punishment faced for fishers acting unlawfully. Where the chance of income outweighs the chance of punishment, IUU fishing techniques are much more likely to be utilized (Funge-Smith). In Cambodia, the lack of catch monitoring and enforcement of fisheries laws leads to a very low likelihood of punishment in any form. Fishing vessels operating unlawfully reduce costs in terms of licensing, registration and vessel specifications (SEAFDEC 2016a). They also may ignore catch quotas, enter closed fishing areas, and target undersized or rare species, increasing potential income. As an example of this, Thai and Vietnamese vessels frequently enter Cambodian waters for fishing, contributing to the overcapacity issues (Bangkok Post 2009; Styllis & Sothear 2014). According to Article 38 (see ‘Article 38’ pp. 43) of the ‘Law on Fisheries’ (FiA 2007), foreign vessels fishing in Cambodia must be under agreement with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries after gaining approval from the Royal Government of Cambodia. Cleary this law is poorly imposed on foreign vessels, however its enforcement would undermine IUU fishing in the Kep Archipelago. Overall, domestic and foreign fishers face minimum incentive to fish lawfully, thus they may be driven to adopt IUU fishing techniques.

The presence of open-access fisheries (OAFs) in Cambodia greatly hinders efforts to combat IUU and overfishing. Owing to the lack of regulation in OAFs, fishing intensity is typically higher than the socially optimal level, economic profits from fishing are dissipated, and marine stocks are degraded or even driven to extinction (Fuller et al. 2013). Clearly, OAFs are not sustainable or cost-effective. The proposed MFMA seeks to establish regulated zones, which will overcome the issues faced and consequences caused by OAFs. Together with improved fisheries law enforcement, vessel registration and formation of monitoring system, the impacts OAFs have caused environmentally, socially and economically, will be rectified by this MFMA.

Vessel registration and Monitoring Control & Surveillance (MCS):

As it stands currently, Cambodia faces numerous issues with boat licensing and registration. Relatively few vessels apply for a fishing license, the enforcement of licenses is inadequate and additionally, fishers generally do not have any rationale for acquiring a fishing license (SEAFDEC 2016d). Presently, the improvement of law enforcement and the distribution of information to boat owners regarding fisheries laws are being attempted in an effort to resolve these issues. This is important, given that the lack of a license and the non-payment of fishing fees by non-subsistence fishers is illegal according to Article 32 and 45 (see ‘Article 32’ and ‘Article 45’ pp. 43) of the ‘Law on Fisheries’ (FiA 2007).

‘Monitoring and control on fishing vessels registration’ forms no. 3. 2. 5 of the Annual Work Plan (AWP) 2016 for the FiA (FiA 2016). Cooperation between the FiA and other relevant authorities is required, for instance with the Marine Police and regional Fisheries departments. Additional support may also be required by relevant agencies, given that limited budget and manpower is one of the challenges faced in combatting IUU fishing (SEAFDEC 2016b). Together, these agencies can cooperatively develop greater levels of licensing and registration, whether by information dissemination or enforcement of relevant fisheries laws. Importantly, vessel registration allows for an MCS system to be established, a key step towards achieving sustainable fisheries. A MCS is defined as follows (FAO 1981);

Monitoring: the continuous requirement for the measurement of fishing effort characteristics and resource yields;

Control: the regulatory conditions under which the exploitation of the resource may be conducted; and,

Surveillance: the degree and types of observations required to maintain compliance with the regulatory controls on imposed fishing activities.

In a fisheries context, the purpose of a MCS system is to ensure that control measures, once agreed and adopted, are sufficiently implemented (Bergh & Davies 2002). Abiding by conservation measures is vital to the effective management of fishery resources. MCS places emphasis on encouraging compliance by fishers, as opposed to enforcing regulations upon them. However, the consequences of non-compliance must be fairly established relative to the effect they will have on the fishery. In the case of the proposed MFMA, fisheries laws against IUU fishing should be strongly enforced, whilst small-scale sustainable fishing should be encouraged.

MCS systems assist in achieving compliance with measures by providing feedback and information to the management strategy, which can be used to focus on compliance issues or otherwise. MCS information may be collected from official landing ports where catch monitoring can be recorded. Catch monitoring, a key aspect of MCS, provides essential information regarding catch quantities relative to fishing capacity (FiA 2016), as well as trends in the size and population of marine stocks. Unfortunately, owing to little official data on fleet composition, fishing effort and marine catch in Cambodia, it is not feasible to perform an assessment of fishing capacity (FiA 2016). Bearing in mind that the assessment of Cambodia’s fishing capacity is considered to be the first step towards developing a National Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (NPOA-IUU), the need to implement MCS is of great significance (National FiA 2016).

Importantly, catch monitoring also hinders IUU fishing vessels, which lack registration and thus cannot dock at official landing ports where catch monitoring is conducted. The issue of IUU fishing products entering the market is addressed in the ´ASEAN Guidelines for Preventing the Entry of Fish and Fishery Products from IUU Fishing Activities into the Supply Chain´ (SEAFDEC 2016a). One of the primary objectives of these guidelines is to establish strategies and measures to prevent the entry of fish and fishery products from IUU activities into the supply chain. MRAG (2009) estimated the annual production from IUU fishing activities to be between 11 and 26 million metric tonnes, accounting for 10 to 22% of the world’s total fisheries production, and valued around US$9 to 24 billion per year. In Southeast Asia, some studies estimate the total IUU fisheries production to be valued close to US$5.8 billion (SEAFDEC 2016a). Clearly, this issue is pervasive and desperately needs combating via policy and ground-level changes, which a MCS framework will provide. In addition to this, fisheries MCS by Cambodia would align its interests with that of the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (Bergh & Davies 2002). This infers that implementation of the proposed MFMA aligns regional and national action with international instruments, i.e. the United Nations (UN).

As part of these ASEAN Guidelines, a strategy for data collection and reduction of IUU fishing is the ASEAN Catch Documentation Scheme (ACDS). The ACDS aims to improve the traceability of fishery products, the credibility of fishery products for intra-regional and international trade, and additionally prevent the entry of IUU fishery products into the supply chain of AMS (SEAFDEC 2016a). Following the principles outlined in the ACDS would greatly improve Cambodia’s catch monitoring and ease of fisheries law enforcement. Given Cambodia’s red card status with the European Union (EU) since November 2013 (European Commission 2015b), the scope of its international fisheries trade is limited. However, with the establishment of the ACDS and other sustainable policy and practical changes, for instance the implementation of the proposed MFMA, Cambodia could expunge its red card. Supporting this, in December 2014 Belize had its red card rebuked, after adopting ´lasting measures to address the deficiencies of its fisheries systems´ (European Commission 2015a). By following Belize’s lead, Cambodia as a whole could reap vast economic benefits for Cambodia, especially for fishery industries.

Cambodia is one of eleven countries that provides technical advice and assistance for the Regional Plan of Action (RPOA) to Promote Responsible Fishing Practices Including Combating Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing in the Region (RPOA-IUU 2016). Notably, SEAFDEC is one of four organizations that fulfils a similar role. The RPOA aims to sustain vital fishery resources through the strengthening of fisheries management and the promotion of sustainable fishing practises in the region. Actions consist of conservation of marine resources and their environment, management of fishing capacity, and combatting IUU fishing in specific regions, including the Sub-Regional Gulf of Thailand. These actions are vital to ensuring food security and poverty alleviation in the region. The formation of the proposed MFMA would align Cambodia’s regional actions to that outlined in the RPOA, a vital step in developing sustainable long-term fishing practises. In turn, adopting the RPOA in Cambodia would set the foundation for embracing larger national and international instruments, for instance the developing NPOA-IUU, and the International Plan of Action (IPOA) to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing’.

The Kingdom of Cambodia’s Law on Fisheries (2007) – Laws Applicable to Fishing Activities in the Kep Archipelago:

Chapter 3 – The Fishery Domains:

Article 11:

The Marine Fishery Domain refers to marine water or brackish water that extends from the coastline at the highest high tide of the coastal lines to the outer limits of the EEZ of the Kingdom of Cambodia.

The Marine Fishery Domain is divided into:

– Inshore fishery area, which extends from the coastline at higher high tide to the 20m deep line.

– Offshore fishing area, which extends from the 20m deep line to the outer limits of the EEZ of the Kingdom of Cambodia.

– Fishery conservation area, seagrass area, and coral reef area which are habitats for marine aquatic animals and plants.

– Mangrove forest area including mangrove and forest zone which are important feeding and breeding habitats for aquatic animals, and protected inundated areas.

Chapter 5 – Protection and Conservation of Fisheries:

Article 20:

All kinds of fishery activities in the fishery domain by using the following gears shall be absolutely prohibited:

1 – Electrocuting devices, explosive stuff or all kinds of poisons.

4 – Spear fishing gears, Chhbok, Sang, Snor with projected lamp.

6 – Net of all kinds of seines with mesh size of less than 1.5cm in inland fishery domain.

8 – Pair trawler or encircling net with attractive illuminative lamp for fish concentration.

Article 21:

Producing, buying, selling, transporting and storing and electrocuting devices, all type of mosquito net fishing gears, mechanised motor pushed nets, inland trawler that are used for fishing purpose shall be prohibited.

Article 23:

The following activities are permitted under permission:

2 – Transporting, processing, buying, selling and stocking endangered fishery resources.

6 – Buying or selling ornamental shells of rare species.

Chapter 7 – The Management of Fishery Exploitation:

Article 32:

All types of fishing exploitation in the inland and marine fishery domains, except subsistence fishing, shall have:

1 – To get a fishing license.

2 – To pay tax and fishing fees to the state.

3 – To follow the regulations stipulated in the fishing license.

The hiring of fishing lots for exploitation can be undertaken through investment, public bidding or hiring, by agreement for those fishing lots, which have no bidders interested in bidding.

The legal procedures for investment, public bidding, hiring by agreement, and payment of fishery fees shall be determined by sub-decree.

Chapter 9 – Marine Fishery Exploitation:

Article 45:

All types of fishery exploitation in the marine fishery domain, except subsistence fishing, shall be allowed only in the possession of a license and these exploitations shall follow the conditions and obligations in fishing logbook.

The model of the fishing logbook shall be determined by the proclamation of the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Article 47:

Fishers shall tranship fisheries products at a fishing port determined by the FiA.

Foreign fishing vessels that are permitted to fish in the marine fishery domain shall inform the FiA prior to port calls in marine fishery domains of the Kingdom of Cambodia.

Other terms and conditions on transhipment of fishery products and anchoring of the foreign fishing vessels shall be determined by the fisheries administration.

Article 48:

Based on precise scientific information that the fishing practises have been or are being the cause of serious damage to fish stock, the FiA has the rights to immediately and temporarily suspend fishing activities and propose for a re-examination of the fishing agreement in order to seek for the decision from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Article 49:

Trawling in the inshore fishing areas shall be forbidden, except for the permission from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries at the request of the FiA to conduct scientific and technical research.

Article 50:

All fishing vessels which are not licensed to fish in the marine fishery domain shall not keep their trawl fishing gears stowed in a manner that they are ready for fishing.

Article 52:

Shall be prohibited:

1 – Fishing or any form of exploitation, which damages or disturbs the growth of seagrass or coral reef.

2 – Collecting, buying, selling, transporting or stocking of corals.

3 – Making port calls and anchoring in a coral reef area.

4 – Destroying seagrass or coral by other activities.

All of the above activities mentioned in points 1, 2 and 3, may be undertaken only when permission if given from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Chapter 15 – Penalties:

Article 103:

Any of the following activities committed by the Fisheries Administration Officer shall be considered as an offence and shall be subjected to an imprisonment from 1 to 3 years and can be fined from 5,000,000 to 50,000,000 Riels:

1 – Provide any permission against this laws.

2 – Participate in full or in part and directly or indirectly in any activity or fishery exploitation against this law.

3 – Forgive any fishery offence class 1.

4 – Running the fishing lot either as owner or a share-holder while being a civil servant.

5 – Do not timely report or complain the fishery offence class 1 which appears in their competence.

6 – Intentionally neglect in fulfilling duty or deceivingly give wrong information in writing, which causes the fishery offence class 1.

Marine Conservation is actively involved not only on the ground dealing with the frontline issues of foreign and domestic IUU incursions, we are also involved in the policy making processes. Our Founder/Director has been invited to speak as an expert on Cambodian IUU issues at both a national level and ASEAN level and currently sits as co-chair on the national fisheries sub-committee on IUU. Assisting Cambodia on its reforms within the fisheries sector and very specifically on addressing the current issues of IUU that are affecting Cambodia’s marine resources.

Since 2008 we have been campaigning against the unsustainable and destructive bottom trawling in the shallow waters of Cambodia, that continues to devastate Cambodia’s Marine Resources , According to Cambodian Fisheries Law Bottom Trawling is outlawed in all marine inshore areas, that means any areas shallower than 20m from the high tide line, this can be found in the revised 2006 Fisheries Law, under article 49, and Inshore areas are classified under article 11 as seen below.

Since 2008 we have been campaigning against the unsustainable and destructive bottom trawling in the shallow waters of Cambodia, that continues to devastate Cambodia’s Marine Resources , According to Cambodian Fisheries Law Bottom Trawling is outlawed in all marine inshore areas, that means any areas shallower than 20m from the high tide line, this can be found in the revised 2006 Fisheries Law, under article 49, and Inshore areas are classified under article 11 as seen below.

Article 49.

Trawling in the inshore fishing areas shall be forbidden, except for the permission from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries at the request of the Fisheries Administration to conduct scientific and technical researches.

Article 11.

The Marine Fishery Domain refers to marine water or brackish water that extends from the coastline at the highest high tide of the coastal lines to the outer limits of the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Kingdom of Cambodia. The Marine fishery domain is divided into: -Inshore fishing area, which extends from the coastline at higher high tide to the 20 meter deep line. – Offshore fishing area, which extends from the 20 meter deep line to the outer limits of the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Kingdom of Cambodia.

After Moving to Kep we also found that the trawlers here not only Trawl in areas Shallower than 20m, but that Kep’s Waters (home to some of the largest Seagrass beds in SE Asia) are no deeper than 10m anywhere within the provincial waters. Now before you start thinking how awful the government or the authorities are for allowing this, you must first understand that until Thursday the 3rd of December 2015 Kep only had 4 officers and no patrol boat to tackle this issue, they had to rely on Kampot to send its boats and officers, which could take anything from 1-3hrs to arrive. When Kampot would run fisheries patrols a network of informants would inform the illegal fisheries and they would have time to head in and cease their activities leading to the conclusion that Kep had very little illegal fishing, but it was quite the opposite, infact it is well organised and has been run almost under cover for the past 10 years. Only because we are out there on the water everyday and every night, has it become clear to the extent of the problem and the damage it is causing. Our work and that of the previous volunteers has led not only to the creation of Keps own Fisheries office but also to provincial support on a major crackdown on illegal fishing.

After Moving to Kep we also found that the trawlers here not only Trawl in areas Shallower than 20m, but that Kep’s Waters (home to some of the largest Seagrass beds in SE Asia) are no deeper than 10m anywhere within the provincial waters. Now before you start thinking how awful the government or the authorities are for allowing this, you must first understand that until Thursday the 3rd of December 2015 Kep only had 4 officers and no patrol boat to tackle this issue, they had to rely on Kampot to send its boats and officers, which could take anything from 1-3hrs to arrive. When Kampot would run fisheries patrols a network of informants would inform the illegal fisheries and they would have time to head in and cease their activities leading to the conclusion that Kep had very little illegal fishing, but it was quite the opposite, infact it is well organised and has been run almost under cover for the past 10 years. Only because we are out there on the water everyday and every night, has it become clear to the extent of the problem and the damage it is causing. Our work and that of the previous volunteers has led not only to the creation of Keps own Fisheries office but also to provincial support on a major crackdown on illegal fishing.

With that in mind, add to the fact that many of the Illegal trawlers are also using a system of electric that passes up to 1000 volts through the net to the sea floor, electrocuting everything within a few meter radius of the electric current.

With that in mind, add to the fact that many of the Illegal trawlers are also using a system of electric that passes up to 1000 volts through the net to the sea floor, electrocuting everything within a few meter radius of the electric current.

Electric is also outlawed in Cambodia under Article 98. As a class 1 offence it carries the highest penalty of any fisheries offence.

Article 98

Shall be penalized under the fishery offences class 1 by imprisoning from three to five years and all evidence shall be confiscated for state property or destroyed and terminated of all agreement, licenses for any person who commits one of the following offenses:

4. Fishing with electrocuted fishing gears, explosive and all kinds of poisonous substances in the fishery domains.

They also then trawl straight through Kep’s Seagrass Beds ripping up vital habitat and taking with them any living creature bigger than 1cm, Trawing through Seagrass is also outlawed under Article 52.

They also then trawl straight through Kep’s Seagrass Beds ripping up vital habitat and taking with them any living creature bigger than 1cm, Trawing through Seagrass is also outlawed under Article 52.

Article 52. shall be prohibited:

1. Fishing or any form of exploitation which damages or disturbs the growth of sea grass or coral reef.

2. Collecting, buying, selling, transporting and stocking of corals.

3. Making port calls and anchoring in a coral reef area.

4. Destroying sea grass or coral by other activities.

The Fisheries Administration is desperately trying to tackle this issue, but even now with slightly more than their original limited resources and manpower it is a very very difficult job, Thats were we come in, Marine Conservation Cambodia and our volunteers patrol the ocean within Kep Provincial Waters and report all offences back to the fisheries department, after taking photos and video, and often chasing the trawlers out of the most sensitive areas. We also often have fisheries officers stationed at our project base, who together with our team can directly arrest illegal fishers and confiscate their illegal equipment before they have time to escape with their haul.

You can check out some of the pictures from the patrols here, and read some of the blog posts from previous volunteers here

We have also gained a lot of media attention and you can see some of the recent articles from 2015 below

The current costs for staying with us vary depending on your length of stay, your experience and what you can personally offer to our project.

You can find other programs in Cambodia both more and less expensive than us. But we guarantee, you will clearly see where your money goes once you arrive, as mentioned in other areas of our website we are fully self sustaining, we havent secured any research grants yet, we rely on the fees we charge to be able to accomplish the objectives asked of us by the Royal Government of Cambodia and our own project goals and objectives.

The weekly fee covers all of your accommodation, food, diving (excluding courses) and other direct expenses needed to support you during your stay. It also includes a small amount that goes to cover project costs such as the Khmer staff wages, running and maintenance costs such as boats, electricity, water and materials needed to conduct the research.

We do NOT use any of your fee to cover administration costs, advertising costs or foreign staff wages.

For stays of 2 weeks or less, the weekly fee is 500$.

For stays of 3 weeks, the weekly fee is 400$.

For Stays of 1 month the Weekly fee is 350$.

With each addition week after 1 month costing 300$

From experience we have found that volunteers that can offer us more time are able to make the biggest impact, so for stays longer than 2 months, please contact us to work out a cost that can suit your budget whilst still allowing us to operate effectively.

If you’re an experienced academic or professional, please contact us at seahorseconservation@gmail.com so we can discuss how to best use your skills.

For Khmer students we do offer full scholarships, please apply to find out more.

Priority Work Happening Now

The Cambodia Marine Mammal Conservation Project

In September 2017 MCC initiated Cambodia’s first long term study investigating coastal cetacean species.

The project is combining boat and land surveys with photo-identification techniques to investigate abundance, distribution and residency patters for cetacean species encountered in Cambodia’s Kep Archipelago, namely the Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris), Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) and Indo-Pacific Finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides). Gathered data will be used to identify critical habitats for feeding, socializing and resting for each species, with this information ultimately being used towards the establishment of informed cetacean management strategies.

If you are interested in joining our dolphin research team, please apply through the application form in the ‘contact us’ section.

Ongoing

We are just beginning a whole new stage in the development of our conservation efforts in Kep province. Our MFMA (Marine Fisheries Management Area) zoning proposal has been accepted and over the next few months we will be adapting finalizing our current management plan, this includes registration of fishers, catch monitoring, demarcation, quotas on size and sexual maturity, and a full MCS program to deter and stop any IUU activities with in the proposed zones.

We need Volunteers with Experience or Interest in MPA or fisheries resource management right now.

Volunteers with Experience or Interest in IUU (Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported) fishing and MCS (Monitoring Control and Surveillance).

We are currently working on many reports directly relating to these current issues.

This is a great opportunity to be directly involved in on the ground activities, our work makes a direct impact. And the work you would be contributing to, is history in the making, after our work on Cambodia’s first ever MFMA, this will be the second, the management of this smaller area will be faster and easier to implement and also allows us more freedom to think outside the basic management structures and trial a series of restoration projects.

MFMA Demarcation and Habitat Restoration

Many studies indicate that Commercial and Non Commercial marine species can be increased significantly with the introduction of fish aggregation devices, artificial reefs, and Oyster and Mussel reefs/beds. A large scale project to reestablish and increase the quantity of Oyster and Mussel reefs/beds in Kep province will significantly benefit local communities by providing natural aquaculture opportunities for harvest. In turn, these reef systems will provide habitat and food sources resulting in an increase in commercially fished marine species and biodiversity, thereby providing increased livelihoods for small scale local fishers, and possible alternative livelihoods for local IUU fishers. Additionally, restored and enhanced Mussel and Oyster reefs will allow for potential private sector opportunities for commercial aquaculture, such as pearl and seaweed farms etc. These opportunities will be integrated into zoning and management schemes created during the implementation of this project, which will support existing coastal management plans. See more here.

Ongoing

Right now we are in the process of some ground breaking Seahorse Research.

This is happening right now, together with Dr. Tse-Lynn Loh and Lindsay Aylesworth from Project Seahorse and Shedd Aquarium, we are working on a large project to assess not only the seahorse populations around Kep but also look at how Seahorse data is collected and running tests on occupancy and sightings within different habitats and how different levels of experience within research teams effects data collection, this is very exciting and ground breaking work which has never been done before. Over the next few months we have a lot of data to collect from 3 main marine habitats, Seagrass, Benthic Shell cover, and Mud sites, on top of this we have 3 sites for each Habitat, Protected, Semi Protected and Not Protected. We are also currently working on a Tagging program looking at 2 study sites with around 10-15 resident seahorses.

Our Seahorse Research has been featured in National Geographic you can read the article here

An National news article about the beginning of our Tagging work can be found here

For more information on methodology and how to get involved in this research please contact us.

Also right now is our socio-demographic community fishing interviews, covering many aspects of resource management and fisheries research.

Over the past year we have been visiting 4 fisheries communities within Kep Province, each visit we run interviews with local fishermen covering, catch sizes, past and present problems and conflicts, livelihood, aquaculture, conservation of resources and habitats, the questionnaires work not only for us to gather much needed information but also help to highlight areas where we can educate and also our presence helps to empower and give confidence to those fishers who understand the need for conservation and want to get involved, all of this is done in a relaxed setting with the community often at the fishers home. Over the last month we have been interviewing some of the illegal fishers, very interesting as some are ones that recognise us as the people that caught them, and this leads to some very interesting discussions and insightful information, this work is ongoing and the statistical analysis of this data and the write up of the report is ongoing.

Some photos of the community interviews can be seen here.

For More information on this aspect of our work please contact us.

Artificial Reef and Underwater Gardens

This is a continuous and ongoing project that is both fun and includes longterm research, including pathways that help to stimulate new coral growth, fleshy algae and seagrass beds, this is a real underwater garden that can be studied and enjoyed as an underwater gardener. This is all run with strict guidelines and is showing some great results.

6 Monthly Coral Reef Surveys and House Reef Mapping

Every 6 months we run a series of Marine Reef Surveys covering the Islands of Koh Angkrong, Koh Mak Prang and Koh Seh, These usually take around 3 months to complete and of course are weather and sea condition dependant.

After Matteo’s return with an amazing mapping program he designed specifically for the study of our house reef, we can now map 1mx1m across our whole house reef and house seagrass beds, covering an area 150mx300m. With detailed squares showing everything from percentage coral and seagrass cover, to species diversity, this project will take us at least the next year to complete if not longer, and once finished, we have a baseline to start all over again to monitor changes.

Other Research and Potential Projects

These are our current projects which are run daily and have a set timeline to be completed, all of our team are involved in this work and this is where we need volunteers and interns the most, especially the Seahorse and community work. We are not limited to just these activities but it is where we need assistance right now to compete them within our timeframe, We also have 6 monthly Reef surveys and other periodic work that must be completed, and this post will be updated as needed.

We are also looking for people to independently study the wide variety of Seagrasses and Algae’s that we have, and also to continue our species database for Kep’s ocean.

We started small, but as the time has gone on we have managed to move on from patrolling and diving from small rented boats to our very own fleet, we call them the small, medium or large boat, or refer to them by the captains name such as Phon’s Boat. Each vessel is fully registered and well maintained as they are needed for patrolling, diving and our supply and pick up runs to the mainland.

The largest boat is 20mx5m and is the jewel of our fleet,

Next is the medium boat around 14mx3m and the most used of our boats,

The Speed boat was donated by ICFC and is our fast response patrol boat and also there in case of any emergencies. We recently acquired a brand new 250hp Suzuki four stroke engine.

Our marine research is very important so our scuba diving equipment is kept well maintained and there is a good selection of sizes, we all love to dive so everyone takes a hand in making sure the dive shed is looked after, for refills we run two large Bauer air compressors each of which is serviced yearly and has regular filter and oil changes. We all dive so we want our air to be tasting and smelling good.

Koh Ach Seh Island is located in the southern part of Kep Province. The little town of Kep is the closest populated area to the island. By boat it takes roughly 1 hour to reach Koh Seh from the Pier in Kep, but that can change depending on weather and sea conditions. The Cambodian forces used Koh Seh as an outpost during the war with Vietnam. It is the furthest island from the mainland, in the area, and the closest island to Vietnam. The island is uninhabited except for a small marine police station and of course Marine Conservation Cambodia. A lush tropical paradise, the island is full of fruit tress, which were planted as a food source by the Cambodian forces, and scattered with old military bunkers as well. The MCC base is located in a small but protective cove offering us shelter form the weather especially during rainy season. The little bay also contains our home reef, which provides the MCC team with a beautiful reef to explore and survey without needing to take a boat ride. It is a shallow reef, but given it is close to shore it offers calm waters making for enjoyable safe diving conditions. These conditions are also extremely helpful in training new divers and collecting crucial data from surveys. The island has many walking trails allowing for beautiful nature hikes or a walk up the hill to catch a sunset. Koh Seh is a small island only taking a little over an hour to walk around depending on the tides.

Besides being responsible for the management and protection of Koh She, Marine Conservation Cambodia is also responsible for 13 other island reefs in the area. Along with these 13 other reefs MCC maintains roughly 3000ht of seagrass beds within Kep Province. These costal waters in Kep Province are home to a vast diversity of marine life. Dolphins, turtles, sea horses, crabs, and countless other species can be found in these waters, making it a beautiful place to call home.

The town of Kep is roughly a 3-hour drive from Phnom Penh; roughly 2 hours form Sihanoukville, and roughly 30 minutes from Kampot. There are multiple ways to get to Kep including private taxi, bus, or Tuktuk. It is an extremely friendly, safe, peaceful, and relaxed area of Cambodia. On the weekends you will find many locals from Phnom Penh coming to Kep in order to escape the hustle of the city. There is a small but beautiful beach in Kep, along with restaurants, and accommodations. A few stores and markets litter the streets making Kep a great place to stroll around and take in the culture. There is very limited shopping and almost zero nightlife in Kep, but that just adds to the relaxing sleepy feel of the town. With a beautiful national park only minutes away or the bustling crab market, there is plenty to explore.